On Africa Freedom Day, I’m thinking of Betty Kaunda, Zambia’s first First Lady, who embodied what it meant to be a revolutionary partner. After working on the Cecelia Miller exhibition on Zambian monumental history, I’ve been reflecting on the actors involved in the independence process. Alongside the well-known male figures, there are powerful women whose contributions to liberation are equally vital.

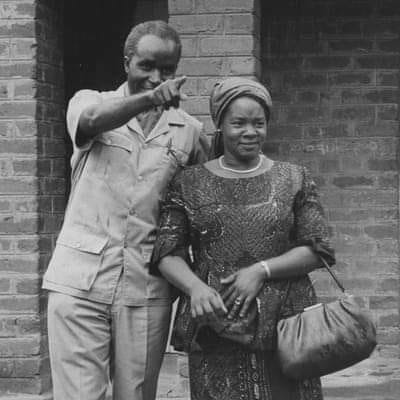

I’ve found myself drawn deeply into Betty’s story, as well as the broader role of the political figures who shape how we remember liberation movements. While her husband is widely celebrated and, admittedly, I’m equally charmed, I wanted to know about her.

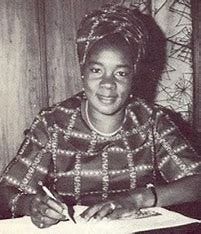

Betty Kaunda, born Beatrice Kaweche Banda in Chinsali, Northern Province of Zambia, is remembered as “Mama Betty”, a mother of the nation, not by ceremony but through action. She helped define what it meant to be a revolutionary partner, walking in lockstep with the liberation movement rather than standing in the shadows.

Betty Kaunda nearly pursued a career as a teacher early in her life, a respected path for women at the time, but her life took a different course when she married Kenneth Kaunda, who would later become Zambia’s first president. Instead, her leadership, deeply rooted in service and mentorship, went on to embody the values of unity and commitment, much like a teacher shaping and supporting her students.

As Kenneth Kaunda faced imprisonment, surveillance, and detention for his involvement with the Zambian African National Congress and later UNIP, Betty held the home front with grace and resolve under extremely difficult conditions. During her husband’s detention, she visited him regularly and served as a calm, resilient public presence, showing colonial authorities that intimidation would not weaken the movement.

Beyond her role as a mother of the nation, she held active roles in the struggle. She played a vital supportive role within the United National Independence Party (UNIP)and its Women’s League, encouraging women’s political participation and helping to anchor the party’s ethos of unity and collective care. She actively sustained the struggle by sheltering activists and freedom fighters operating under the radar, she also delivered covert messages. Despite constant police harassment, she remained steadfast in her belief in justice and independence.

The Matriarch

Unearthing these photographs, I’ve always felt that Betty Kaunda embodied a profound regality and respect. As a couple, Betty and Kenneth Kaunda seemed like true role models. Married for 66 years and parents to nine children, Dr Kaunda often spoke candidly in public about how much he adored her, even breaking into song to serenade her. I suspect that this mirrored the way women are treated in Zambian society till today, where matriarchs hold deep influence, guiding families, communities, and important decisions.

This quiet authority, the soft power, Mama Betty, made leadership look like care. In return, she was widely respected. I don’t think we can take such affection for granted; it was rare to have a First Lady so publicly loved. She was not merely an accessory to power, but a realistic aspiration for women. Her humility in this likeness was her strength, a true example.

Pan African Fashion

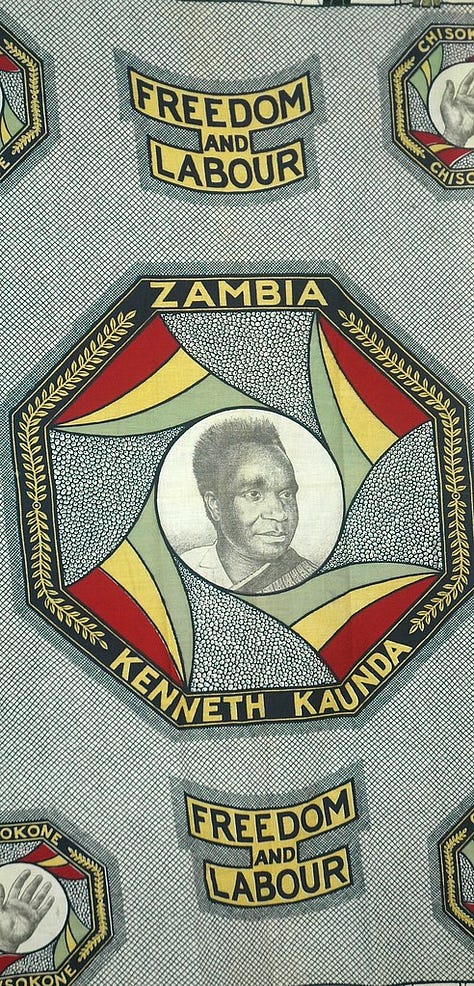

Alongside UNIP’s enthusiasm for pan African liberation, it hosted the ANC headquarters in Lusaka for several years. Mama Betty emboldened a wider Pan-African dignity and strength of women in liberation struggles with her fashion, as a public presence. Rejecting luxury or excess, she often appeared in traditional chitenge, sending a powerful message about simplicity, service, and cultural pride.

Quite the opposite of Grace “Gucci”, I recently came across a TikTok video about the former First Lady of Zimbabwe, whose lavish shopping sprees earned her that famous nickname. Mama Betty, by contrast, exudes humility and grace, standing far apart from the extravagant spending we now generally associate with presidents’ wives. Public money, of course, during her husband’s presidency.

Moreover, the chitenge cloth was more than just fashion during Zambia’s independence era. It was a visual tool of political solidarity, particularly under the United National Independence Party (UNIP). Worn widely by members of the UNIP Women’s League, including figures like Betty Kaunda, the cloth featured slogans, party emblems, and portraits of Kenneth Kaunda. This attire was strategically worn during rallies, public holidays, and community mobilisations, transforming women into visible agents of the movement. It symbolised allegiance, resistance, and pride, uniting women under the call for liberation and, later, for national development. Embodying this pride with grace and grounded, Mama Betty was visibly a rallying point for women’s involvement in nation-building.

Across the continent, fashion was a language of resistance. Women like Ghana’s Ama Ata Aidoo and Nigeria’s Buchi Emecheta used clothing and aesthetics to express political commitment and cultural sovereignty. Nigerian women, too, tailored their wrappers short for movement, pairing them with extra fabric draped over the shoulder or arm and bold, sculptural head ties. These choices were not just about style, they were declarations of identity, pride, and refusal to conform to colonial norms.

Even during official functions and state celebrations, women would wear UNIP chitenges draped elegantly, often with extra cloth carried over the arm or styled into dramatic headwraps. This fusion of politics and fashion marked a period where nation-building and self-expression coexisted—and where women continued to lead, not just through activism, but also through style

Mama Betty Kaunda passed away on 18 September 2012 in Harare, Zimbabwe, while visiting her daughter, Musatilanji Kaunda Banda—affectionately known as Musata. A trained teacher by profession and a national icon, Mama Betty was posthumously recognised in 2023 by the African Union (AU) as a Freedom Activist and founding member of the Pan African Women’s Organisation. She was honoured alongside other women freedom fighters whose contributions have often been overlooked in past commemorations.

This year, the AU’s theme is Reparations, a call to acknowledge and address the enduring impacts of colonialism and systemic injustices across the continent. Reparations, in this declaration, go beyond financial compensation; they encompass justice, healing, and restoring dignity to those and their descendants who suffered under oppression.

I was particularly keen to learn about the cultural pillar and the role of remembering as an act of power, a political and cultural act that acknowledges the realities of injustice and the courage it took to resist them. It was powerful to see how this iconic Zambian woman is honoured within this act of remembrance, as Africans continue to reclaim their stories and strengthen the struggle for justice and equality.

Thank you for reading this far. I jotted down these reflections while working on the Cecelia Miller exhibition and looking at archive footage on Zambia’s rich history and culture. I’m currently working on a couple of articles and Gallivant reviews, but wanted to share some of the lovely photographs and icons that have captivated me recently.

I love the way you put this piece together -- your choice of photos, their arrangement and how the narrative seems so cozily wrapped around them. The varied designs and colors of the chitenges are an especially inspired touch. Outside of textbooks, this is how I want to enjoy our history. It is powerful and factual, yet it has the elements and softness of a bedtime story; a nations founding folklore essentially.

I learned something too. I never for once stopped to think whether "Betty" was in a place of a longer formal name and also the probable reason why they named one of their children Kaweche. And I didn't realize Mama Betty was born in Chinsali too.

Been entertained by the prose and educated all at the same time.