As someone who once protested at one of Europe’s biggest art fairs, I’m wary of them. It’s not just the price tags, it’s the way these fairs revel in excess: niche artworks flown in from around the world, sometimes by private jet, for a spectacle designed not for the public, but for a select, specialist few.

Not to make everything about class struggle, but also yes. The evolving roles, struggles, and dynamics within today’s art system reveal how class struggle continues to play out in the art world vis-à-vis the context of neo-capitalism, where everything meaningful can be commodified.

My fear is that art, at fair scale, is the manifestation of this casino slot machine: money goes in, and out comes the artist producing. This production of beauty is often highly niche, created for the highest bidder, who pays to add “beauty” and value to their life. The bourgeois call it “elevated living”.

The buyers at fairs are not everyday art lovers. But in reality, many arrive in fast cars, not to appreciate, but to acquire, hoarding pieces as “assets.” Don’t get me wrong. I understand that art collecting can be a way to secure wealth. But I also believe in preserving the integrity of art, as craft rather than production, or the emotional or political work it sets out to do.

I want to believe that art should serve its moving, stirring duty first, and if an artist gains success over the years and puts out a thoughtful, well-priced collection, all the better. It’s this second purpose of acquiring art that I remain unsure about. And while it might be naive, I understand that buyers enable an artist’s livelihood. Still, surely it shouldn’t only be the extremely rich who can afford to own art.

It’s also the inherently classist nature of buying art that creates an environment, I feel, that deters many people from engaging with it, so you see, my real problem might be with the bourgeoisie all along. And the snobby gallerist who assesses your outfit or Googles your name before paying you any mind. I found that attitude cold at first, but, strangely, also to my advantage. I've started to enjoy galleries because I’m paid no mind, left alone to enjoy the art on my terms. Still, I have to admit that the museum offers a much more accessible experience overall.

My suspicion is that distinction already hints at who the art fair is really for and shows in the kind of art on display, which I’ve long speculated wouldn’t speak to me. And that cold, nose-in-the-air crowd was exactly what I expected to find at an art fair.

After the event, we spoke briefly. I told her I was looking forward to seeing her new work.

“When?” she asked with a smile.

I hesitated—I knew she had work on display at the fair, which, truthfully, was one of the main reasons I was tempted to go.

“I hope soon,” I replied.

So instead of standing on the outside as a sceptic, on the rare chance that I manifested a ticket, I had to go.

Lebohang Kganye’s light

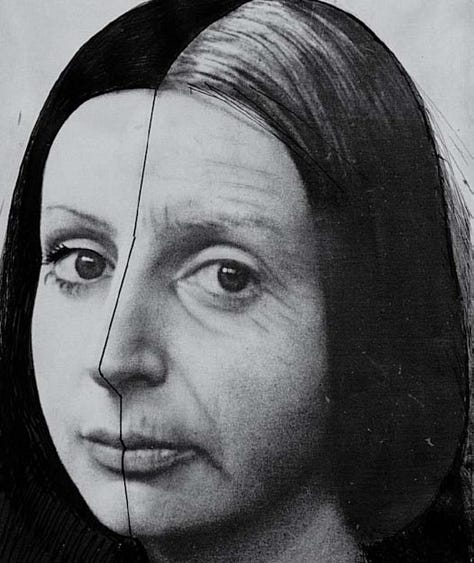

I walked past the champagne bar and the overly commercial displays, weaving through the fair until I reached the Le Parternoir booth. And there, just around the corner, were the large hangings by Lebohang Kganye. Mosebetsi wa Dirithi Kganye extrapolates figures of family members from photo albums to create unique, life-size, textile-based works.

Born in South Africa (b.1990), Kganye began her artistic journey in 2010, shortly after the passing of her mother. That loss sparked a personal pilgrimage across the country, where she gathered family stories—fragments of memory and experience that continue to shape her work today. Through her family history, Kganye explores South Africa’s political past and its resonances in the present. Her works embody this passage of time, of identity, of memory.

After hearing a woman comment Ah, very nice fabric as if not knowing how to engage otherwise. I thought again about value, who assigns value, at what level, and which depths remain unacknowledged or unattained by the public?

During the Q&A at A foundation, I had Kganye asked;

Your very personal work is doing well in Europe, yet its context, the nuanced implications of apartheid in South Africa, isn’t always apparent to the public. There’s a kind of dissonance here, juxtaposed with how open and emotionally resonant your work is. Perhaps the public’s inability to grasp these subtleties reflects a broader deficit, I wondered whether this is a cost artists are aware of.

Kganye felt it’s not always the artist’s task to over-explain to the public. Maybe this is where those writing about the work come in, she suggested…to do the long-form labour of contextualisation. (I loved this wink—also an acknowledgement of the labour already carried out by the artist in making the work itself.)

For her, the challenge lies in rendering that feeling into something three-dimensional, like the curfew lights in her Le Parternoir exhibition. In apartheid South Africa, curfew lights were used to control the movement of the Black population at night, a haunting reminder of surveillance and spatial restriction.

Her last name, fittingly, also means light. Mosebetsi wa Dirithi translates as “the work of shadows” in Sesotho.as she brings light and life to layered postcolonial histories is an animating thread in her practice

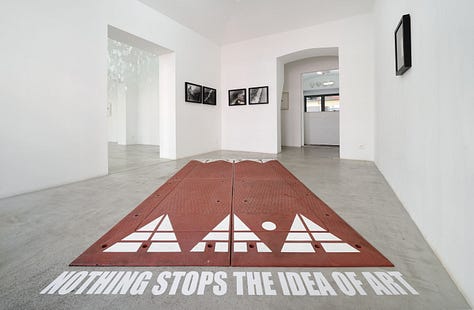

Nadim Choufi ‘s Diplomatic Bestiary

“Radical” work I was not expecting to see at an art fair was Nadim’s work. Josilda da Conceição represented a solo presentation of Nadim Choufi, a Netherlands-based Lebanon-born artist. I first encountered Nadim’s practice at the Van Eyck Academy, where he was a resident until 2024, developing what would become Diplomatic Bestiary, a series of sculptures completed in mid-2023, tracing the modular legacy to colonial campaign furniture. Originally scheduled to be shown in April 2024, then postponed to October, the exhibition is now on hold indefinitely due to the ongoing genocide in Palestine and the war in Lebanon.

The project explores how diplomacy becomes a material in itself, that warps, mutates, and distorts the people, land, and objects it seeks to govern. And in many ways, the project is undergoing mutation, shaped by the very geopolitical forces it reflects.

I was drawn to the work because it lays bare how easily conceptual peace can be made and just as easily undone. In other pieces, he explores peace missions that, while framed in the language of global development, were fundamentally colonial in nature. His reflections interrogate the malleability of development: who defines its value, and who seizes land under its banner.

Without a sincere commitment to purpose, diplomacy can slip into pure bestiality. Just as furniture can be designed to support or to restrain, so too can diplomacy. What appears functional may, in fact, conceal violence. That duality, and the fragility of our so-called world order, is deeply confronting.

Louise Delanghe’s searching is becoming

Louise Delanghe (b. 1994), a graduate of KASK, Ghent—where I saw many exciting graduates last year, seems part of a breeding ground for work created in the context and relevance of the vibrant present. Inspired by classical paintings of the past, she brings new life to the genre, humorously technical and featuring women prominently throughout her work.

Her reflections on women coming of age offer a refreshing take on what might otherwise resemble classical painting. While technically serious in method, her works are full of surprise in texture, scale, and the comic rhythm of subject engagement. She paints many directions, with some works even transforming into sculptures. Classical scenarios, like “man on a horse”, are reimagined as a woman on a cow, a playful nod to self-portraiture and her upbringing on a farm.

In the work of Delanghe, i see the dance of becoming with the swinging tendencies of being. This body of work is a search through time and space, beginning at the moment of conception, reaching toward endless coloured peaks of womanhood. I enjoyed the honesty of these pains of the unknown, resulting in unexpected paintings whose subject matter embraces awkward tension rather than finalised, perfected beauty.

Her paint moves deftly between light and dark, past and future, memory and longing. What we see are passages of inner interest, shifts that transform into sculptures and paintings made from the material of the moment-like the fleeting instance they try to hold. Turning old wood intocanvasSearching is becoming.

I'm excited to be surprised like this. Her gallery carries the same spirit: an energy of young people bringing youth back into the trade and craft. This feels like a new epoch of painting. I’m keen to visit the gallery and see more of the work on their books.

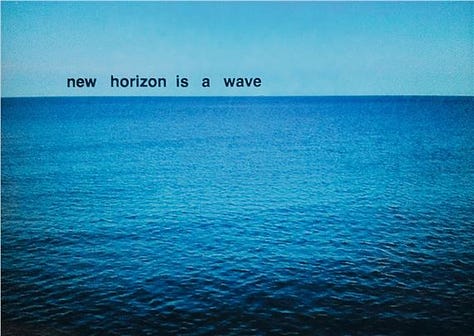

Ewa Partum’s active poetry

Towards the end, I found a conceptual gem: the work of feminist and conceptual Polish artist Ewa Partum (b. 1945). Her practice is about creating signs that lead to more. As acts of linguistic and performative play in search of a new artistic language. Partum believed painting had exhausted its potential to generate new or transformative ideas, turning instead to interventions that questioned meaning, space, and visibility. Her work touches on the notion of public space, female subjectivity, and the political tensions of the 1980s, all with a clarity and quiet force that continues to resonate.

“In Poland, during the seventies, avant-garde art was a male-only domain. ”An example of her pionering is Women, Marriage is Against You! (1980), where she dressed in a wedding dress, wrapped herself in transparent foil, and topped it with a sign that read “For Men.” Then, she cut through the dress and foil, emerging naked, powerfully challenging societal expectations around women and marriage.

Her work reminded me of how I fell in love with art through the Fluxus artists who dealt with the poverty of art, focusing on the transfer of ideas rather than mere objects to consume. Similary, she engages deeply in the ideas of art itself.

Her artistic legacy is carried forward in Artum Foundation along with her daughter, artist Monika Partum, and her work is represented by Ewa Opolaka Gallery in Poland. The gallery was the winner of the 68 Forward Prize at this year’s Art Brussels fair, and rightfully so, for bringing the work of such a giant to the foreground again. I was also in awe of how much of a triumph this was, considering that small galleries bear the cost of attending fairs, which often results in the market being saturated by larger galleries.

if you want to say something , speak in the langauge of the language -Ewa Partum

Overall, not sure if buying art as an extension of lifestyle is entirely wrong, seeing artist benifit from such purchases but I had a great time discovering new work while also seeing some familiar artists exhibited here. While I remain wary, Fairs also feels like a valuable stage to expose a new kind of audience to radical, carefully crafted work that engages deeply with the creation of art itself, exploring art in the language of language.

Other artists I encountered included Cassi Namoda, represented by Xavier Hufkens Gallery, whose vibrant works delve into the complexities of personal identity and history. Additionally, Go Mulan showecased Dion Rosina's compelling pieces, offer profound, jazz-infused photographic paintings inspired by spirituality, alienation, and historical reflections on the African diaspora and the nuances of personal and collective memory.