A satellite dish, deconstructed from its base, likely a high-rise flat, and brought into a small plates wine eatery. Lacquered cream and adorned with LV emblems, its original branding, Sanwei, is turned red à la Supreme. After the first day of Art Basel frolicking, I ended up at an artist-invited, small-group exhibition, among which this “dish” by Shamiran Istifan. Bimbo energy, hip-hop vibes… none of the sort of fashion-police maximalism I’d encountered on the first day in Basel.

For fuck’s sake! The director of a well-known museum had floated past us during lunch, hovering over the ground like an Issey Miyake-adorned monk. If you know, you know type energy, like a normal person…

This is not what I had been looking at all day. But I loved it.

After fair week, I feel the tension of (critical) art within the commerciality of fairs is not just a contradiction but a reflection of the very contradiction we live in. Artists push back and create new worlds, even as the system desperately clings to itself by recycling distractions. I fear that one of those distractions may even be (critical) art itself, as it becomes something to be bought and sold, absorbed into the market it seeks to critique.

I believe this mirrors a broader global struggle between resistance and the forces that suppress it. Where the cost of living continues to rise, basic needs become supermarket hauls, and wars rage on even as sales are made. We are watching images of violence and collapse on our phones while standing in white-walled booths discussing aesthetics. These contradictions aren't just present; they are the conditions of our lives. And artists, knowingly or not, are responding to and shaped by them.

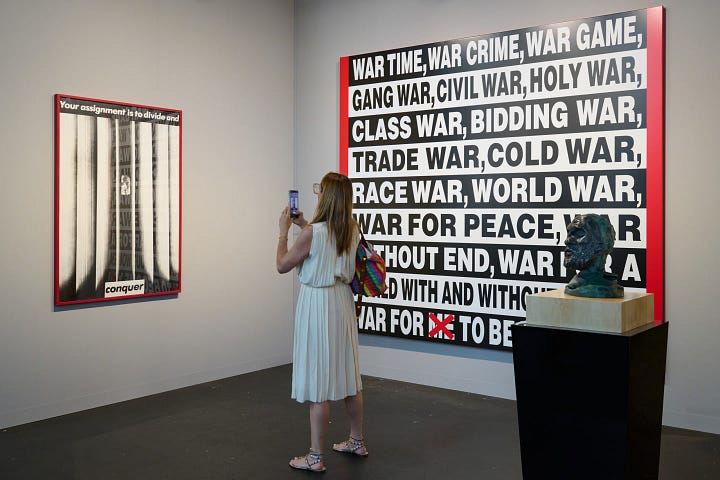

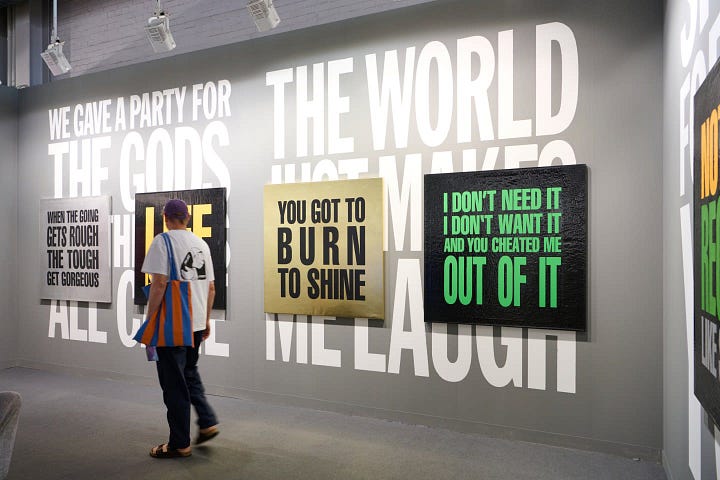

And yes, this is precisely where art’s magic lives. Artists mirror the times and try to communicate the world as we’re living in it: the contradictions, the pressing questions, the joy and the chaos. At its best, art disrupts. I saw many attempts to capture this sense of the disorienting contradictions of our moment.

Across the fairs, I felt this stacking of realities, this tension and interplay, everywhere. The push and pull were palpable in many works. Recurring themes emerged: scale in sculpture, chaos in abstract, the layering cost of past and present, and the whirl of reality infused with subliminal messaging.

The work of Istifan was my first hit of this tension, taking shape in what Jeff Magid recently recalled as “douche bag art.” The term stuck with me: relatable, branded. bold and instantly recognisable, to the common person. This is ready-made art you could spot from ten metres away. The kind of thing that photographs are, meme-friendly, adorned in the iconography of wealth.

The descriptors, visibly expensive, instantly recognisable, and designed to signal wealth, felt the opposite of the art on offer. Instead, the emphasis is on singularity, rarity, and a value that is already known and substantiated before the fair, as seen in works like El Anatsui’s pieces.

Everyday Objects Vuittonified: scale in sculpture.

We live suspended between a longing for beauty and the weight of everyday excess—a contradiction embodied in Shamiran Istifan’s work, where kitsch becomes a language of survival, memory, and misplaced luxury. The Swiss-based visual artist works with Middle Eastern symbolism and modern luxury kitsch. Her objects draw on the symbolism of daily life, showing how banal items become charged with meaning, sometimes even sacred, through the lived impressions of a culture that never set out to define them.

An object not traditionally seen as valuable, like the satellite dishes used by migrant populations to adorn high-rise flats and stay connected with home, is transformed in Shamiran Istifan’s work into a sculptural, marketplace-ready artefact. Her pieces are Vuittonified and Kanye adjacent, but they handle their juxtapositions with intention. They’re not exactly subtle, but they don’t pretend to be selling you something intangible either. Istifan’s work, though glossy, prods at the politics of consumption and asks: whose cultural currency is being put on display and for whom?

Unlike much of what is made primarily to sell at fairs, this year many sculptures felt created to be experienced and felt deeply. I feel the presence of sculptural works, both within and beyond the main Art Basel parcours, signals a shift away from fun-sized, easily movable pieces, toward works that demand engagement and reflection. If not sculptural, the works were large and haunting—figures and texts that occupied space with a powerful presence.

One standout example is Istifan’s double-sided sculptural installation The Lease Is Almost Up, presented at the main Art Basel fair and awarded the 2025 Swiss Art Award. Inspired by Sara Ahmed’s writing on institutional memory, it merges architecture and narrative, incorporating inscriptions such as Girls play here to explore questions of visibility, memory, and who is allowed to occupy space. The work asks whose traces endure, who is rebuilt, and which absences are permitted to be acknowledged.

It reminded me of art’s deeper commitment, not just to beauty or critique, but to recording memory honestly. Which works register the contradictions of our moment, and which ones perform them? Artists, in this sense, take on the role of killjoys. And the killjoy’s commitment, to borrow from Ahmed again, is to expose the problem by embodying the problem.

Istifan’s work does exactly that while still inhabiting the contradiction of being sold. But perhaps that is the most honest position art can take today: sitting inside the system while still holding up a mirror to its absurdities.

Art, Capital, and World-Making: the layered cost of past and present.

Another challenge artists face when engaging with memory is price points. There is a clear awareness of the market dynamics at play within the fair. I’ve been reflecting on how pricing and access remain tightly controlled, and how artists might interpret or respond to this unavoidable reality. In Basel, artists are inevitably positioned within an economy where their work becomes part of systems they sometimes seek to critique.

Taqwa Ali’s, Netherlands-based Sudanese artist's, presence at VOLTA holds pricing constant; her “Mother’s Garden” series engages directly with the contradictions rooted in materiality, economy, and decoloniality. She traces the structural hegemonies of global trade through the very materials she uses—hibiscus and Arabic gum. Both are commonly used in Sudanese art and practices and are historically tied to trade and colonial extraction. In doing so, she draws deep connections between body, memory, and circulation, complicating the very notion of value in the art world.

In her large wooden frames, hibiscus bleeds and stains, leaving behind delicate traces that map how far these histories stretch. For Taqwa, materials carry memory. A ceremonial act, like making hibiscus tea from leaves her mother sends from Sudan, sparked an ongoing reflection on the emotional geographies and inherited ritual materials held. Her presentation in Basel manifests the continuation of trade, but on different terms. Yes, the work is being sold again, but this time, at a (fair) price that acknowledges the labour, the material, and the histories embedded within them.

Another striking exposure of our economic realities is Andrea Fraser’s Index III (2024). The chart in the work suggests it may already be too late to invest in rare whisky. While it critiques banking systems and shows investment in whisky surpassing investment in art, you still find yourself at art fairs where people come to invest. The question becomes—is this chart hyperbole, or are you looking at stock trends right now? That uneasy mix of critique and commerce.

And then there's the cost of hope. At Photo Basel, Gallerist Barbara Polla shared the importance of holding onto hope, past and present. She was referring to the Geneva-based Gallery Analix Forever's presentation of The Beginning of Hope. Among which was an engraved slab by Guillaume Chamahian that gave me chills. A snapshot in time, just as the world was profoundly changed by one man, then taken. “Is that what I think it is?” Yes. But also, a quiet reminder through these images that at the beginning, there was always hope.

Memory, Belonging, and New Narratives: The whirl of reality infused with subliminal messaging.

A highlight was the arrival of Africa Basel, the first edition of this special international contemporary art fair showcasing works and artists from Africa and its diaspora, while making space for creative exchange and dialogue among galleries, collectors, and art enthusiasts, and promoting global interest in African art. The fair’s discussions hosted urgent and generative conversations. Renowned figures such as Ibrahim Mahama, recipient of an ‘Established Artists’ Art Basel Prize, spoke on the evolving infrastructures needed to support African art on the continent. Sammy Baloji, whose practice weaves together research, archival material, and poetic visual strategies, expanded conversations around memory, material, and the role of the artist as witness.

The fair actively reimagined the space contemporary African art occupies, pushing beyond representation toward agency, authorship, and structural change. Without such contextual depth, African art risks becoming a commodity aesthetic rather than a site of knowledge. The fair insisted on that difference.

An example of this insistence is Artworld Passport by Richard Mudariki, created with artHARARE. This satirical project offered limited-edition passports at a consular desk in the courtyard, inviting visitors to apply for a “visa” on-site, for a surprisingly high fee. The cost (400 francs per visa) was part of the critique, drawing attention to the economic and bureaucratic barriers in the art world. Mudariki himself couldn’t attend due to visa restrictions, the very issue his work addresses. He appeared via screen behind the desk, a powerful presence that underscored the work’s message about access, exclusion, and mobility.

The whirl of reality feels especially impermeable in photography. It mirrors what either is or is not. A work either touches you or feels distant, regardless of who is selling it or their intentions for profit. This feeling surfaced again as I wandered through the quieter corners of Photo Basel and Africa Basel, where works by Danielle Dailleux and Nabil Boutros lingered in my mind. Boutros’s 2010 project explored how clothing and appearance in Egyptian society communicate identity and social status, questioning their reliability by transforming himself into various male characters through changes in hair and beard styling.

That tension around identity and appearance resonated strongly because Basel week, in particular, felt like fashion week but for art. The curated looks, even the museum director, who floated like a Miyake monk. Dressing the character felt built in, a performance tied to cultural capital and blurring the lines between art and social signalling.

While Denis Dailleux captured an honest otherworldliness of home and joy.Not Ghana, but that sensation of ease, of flowing. His images are kind and fair, quietly calling you in. Here, the whirl of Jamestown unfolds as fishermen work and children dream. Their fractured narratives and symbolic cues played with disorientation, pulling viewers into reflection or echoing what I’ve come to think of as the whirl of reality infused with subliminal messaging.

Istifan’s work was a welcome anchor during my first Basel experience. Amid the whirlwind, artists continue to leave subliminal crumbs—subtle ideas about value, visibility and cultural capital. These are more than aesthetic gestures; they are notes on art, capital and cultural currency. Ultimately, artists reflect diverse voices, stories and aesthetics, inviting us to rethink what art is and what it can become: a mirror of our contradictions, a form of resistance and a catalyst for change.

The larger question remains: can art be created and circulated outside the entrenched economic systems that shape so much of its meaning and accessibility? What might true pluralism in art markets look like, and how could it reshape cultural dialogue and power dynamics? Fairs like Liste already carry this radicality within, while Africa Basel points to new possibilities, centring dialogue, context and community engagement alongside commerce. These emerging models offer hope that art markets can evolve beyond purely commercial logic and become spaces for critical exchange, representation and reimagination.