I’ve spent the last couple of weeks working on a project with two friends, gladly embracing an era of creative, plotting women, quite different from the “Sex and the City” kind, where the only topic is men. Ours is quite the opposite: we’ve been creating something meaningful together. And as it turns out, we’re the perfect trio: Cecelia Miller, an artist; Sana Ginwalla, a curator; and I, an art writer. Together, we’ve birthed Going to Town, an exhibition about home, history, and keeping infrastructural memory alive.

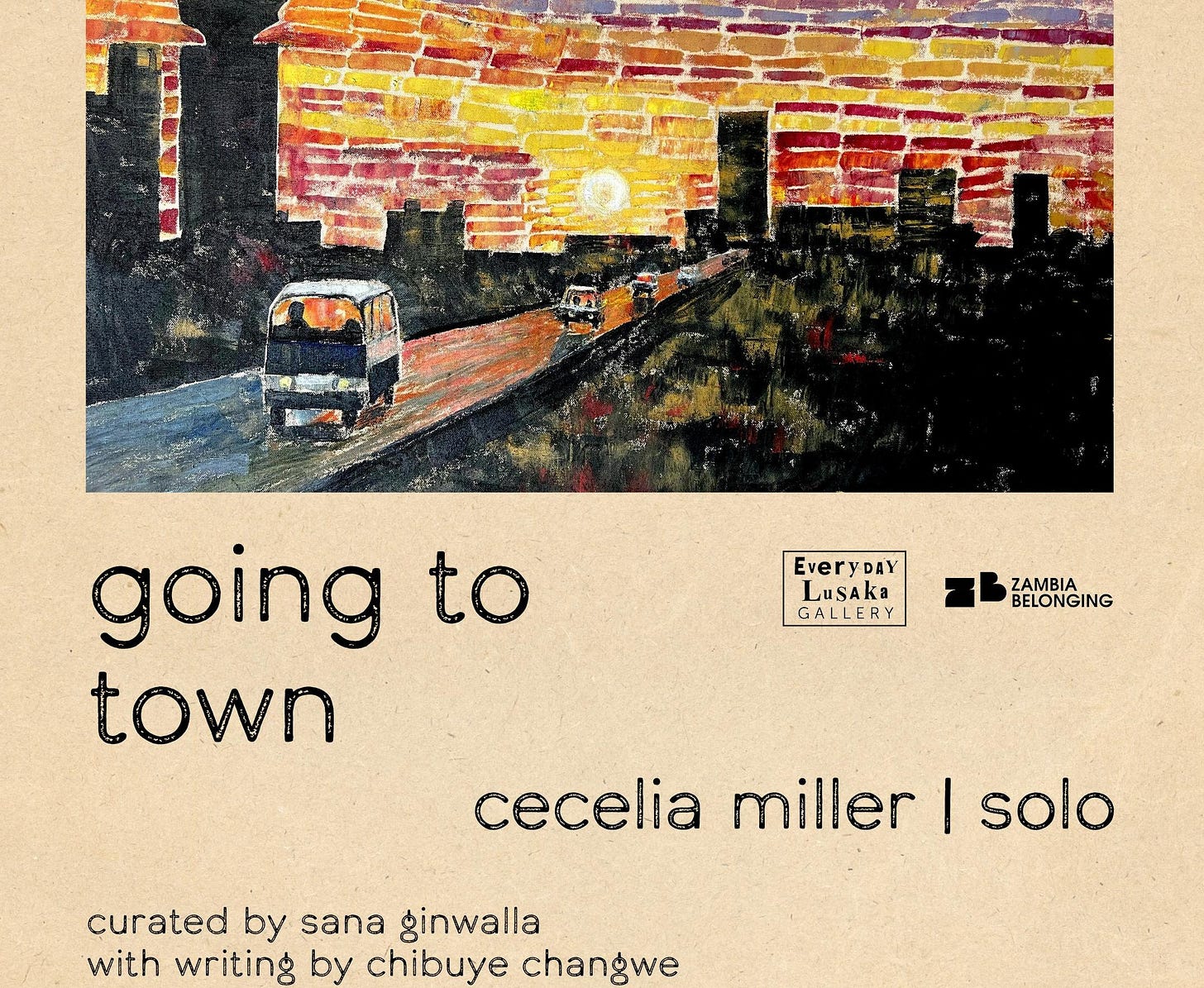

Going to Town is Cecelia Miller’s second solo exhibition. The project uses archival images to reimagine the infrastructural memory of the capital city we all love, Lusaka, Zambia. In her signature style, Cecelia draws on the archive to trace her family history, which is closely tied to Lusaka’s development. To witness this history, one simply has to follow the journey from her family home in Lilayi to the Every Lusaka gallery and then into town.

When we began to think about how we could give words and colour to the story of home, I thought back to my last trip in 2023. Otherwise known as “the summer I quit my job to fully focus on my Summer “(10/10 experience). It was only my second time returning as an adult—I’d left at a young age and always went back with my parents. This trip was different. Over the years, I’d built friendships with people based at home, so I knew where I could land and planned to navigate from there. While fighting off dread about this necessary decision, a profound feeling of belonging gave me purpose and filled a gap I felt in Europe.

The month unemployed came with internal screams and the occasional fear of self-damnation, but I embraced my new role as Minister of Enjoyment, with Rema’s Holiday as my soundtrack. Six full weeks where my roots lie. I passenger-princessed on a road trip through the bush with friends. Between dodging “why are you still single?” blows and chasing gallivant quests, I dug through my grandmother’s political archive and spent time in Lusaka with art bae Sana Ginwalla(the gallerist and Curator of the Bunch), who took me to countless art sites. I bought, arrived, and felt at home. Through city drives, detours, and the friends I made, I carved out my slice of home.

Belonging Through Memory

The title of the exhibition came as I was thinking out loud about how even the most mundane journey, like going to town, came with all the familiar cues of being home.

As a long-time gallivanter, tagging along to run errands with anyone who ventured out was my favourite pastime growing up. Revisiting this activity while home, I noticed with newfound curiosity and listened with sensory sharpness to the urban commotion: the hooting minibuses, street vendors calling out prices, and chance encounters with family members who didn’t yet know I was back in the country. The still-standing colonial-built shop façades lining downtown were etched in my memories like cartoon cowboy saloons.

Going to town was, in a way, going home, with everything that comes with it: unfinished conversations, uncles with layered laughter, and the unshakable sense that memory sits somewhere in the middle, between past and present.

Works like Cecelia’s Freedom House remind me of how belonging finds its way through our roots. I learnt from my grandmother, while eagerly listening to her political commentary (it was election season, after all), that thought-daughtering runs through my veins. She was a political person in her heyday: chairwoman of a district appointed by the United National Independence Party (UNIP), Zambia’s first ruling party after independence. I devoured her stories of the pre-independence Cha Cha Cha campaign of civil disobedience days, rifling through her archive, we came across post-independence campaign time pictures: “And here,” she laughed, “we danced so hard!” A little cocky, she added, “I’m afraid we lost this campaign.” But at peace with that defeat, it had become a sweet memory.

My grandmother’s old stomping ground, also known as UNIP Camp- Freedom House, embodied the party’s humanist philosophy rooted in collective care and African socialism. It became a hub for gatherings and political outreach. Today, it stands as a symbol of Zambia’s political heritage and solidarity with regional independence movements. Its legacy reflects both the fragility and resilience of liberation dreams.

Heritage is Healing

This familial connection is similar to Cecelia’s connection to Zambia. Her forefathers and matriarchs had moved to the country during its boom years—in 1902, when her great-grandfather arrived in what was then Northern Rhodesia as a contracted engineer on the Cape to Cairo railway project. He worked on the line from Livingstone to Lubumbashi, and in 1912, settled the family in Lilayi, where Lilayi Farm, her childhood home, still stands.

It felt natural to explore belonging through history, as identity is shaped by our roots. The making of a person—or a people—is tied to lineage, with ancestral memory still threaded through us. The project took on three layers: historical context, physical infrastructure, and (oral) stories passed down through generations. Reminiscing on everyday encounters, we meditated on how belonging is felt through people and place, especially in a young nation whose foundations remain visible.

Cecelia initially hesitated to place her family history at the centre of the work. The vulnerability of exploring whiteness, belonging, and personal lineage in postcolonial Zambia felt sensitive. But in unpacking her archive, rich with family photographs and memories, she found a language that was both plain and deeply felt. I felt the richness of the story was worthwhile and possible, as the project reminded me of Penny Siopis’s work, a Greek South African artist whose exploration of personal and national memory reveals entangled histories of coloniality, ritual, and accountability. There is something similarly affecting in Cecelia’s gesture: to trace one’s history without spectacle, to hold the past in view while asking what it means to belong now.

A recent post on a popular Zambian forum questioned why the national swimming team at the Commonwealth Games in 2014 appeared overwhelmingly white. The comment section quickly became a reckoning. Someone finally offered: These families have been in Zambia for generations. They’ve contributed, lived, loved, and remained. Their children feel at home.

This untold story of white Zambian belonging, often left out of national narratives, migration as an avenue to generational belonging, was part of what this exhibition hopes to explore. By tracing these connections and celebrating them with care, we sought to tell a complete story of what Zambian belonging looks like.

The Archive is Alive.

The Zambia Belonging Archive became vital, as it documents a lineage often left out of dominant narratives. Initiated by curator Sana Ginwala in 2018, the archive is an ongoing project that gathers personal photographs, oral histories, and objects from people connected to Zambia, creating a counter-archive of home, identity, and belonging. It helped shape this story by offering reference images that could be reflected on with care.

Cecelia is one of four artists who have worked with the archive, but her response is distinct, interpreting archival imagery through painting rather than lens-based media. By blending family archives with painting, she offers a deeply personal reflection on Lusaka’s history.

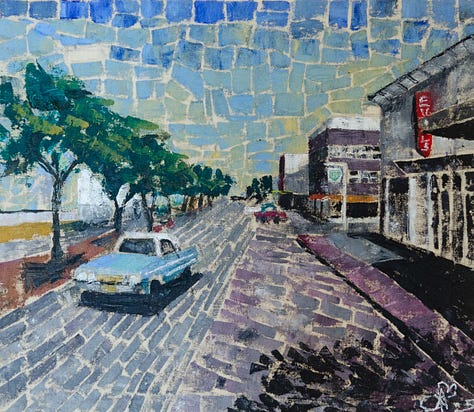

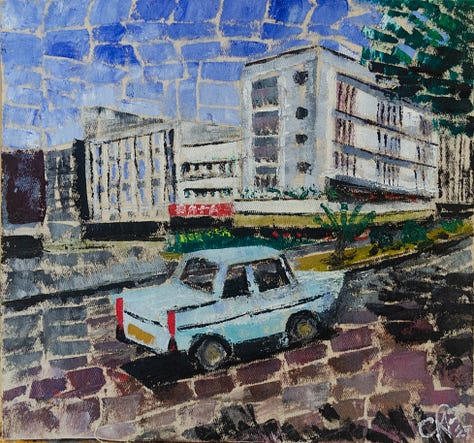

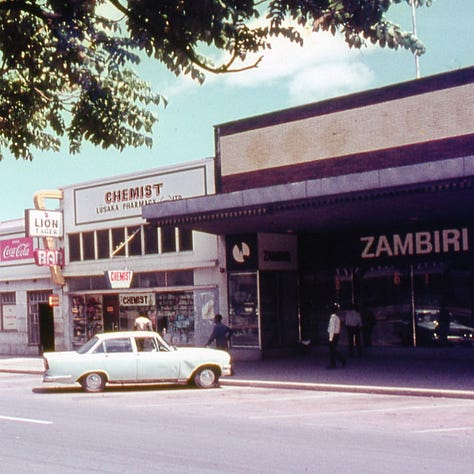

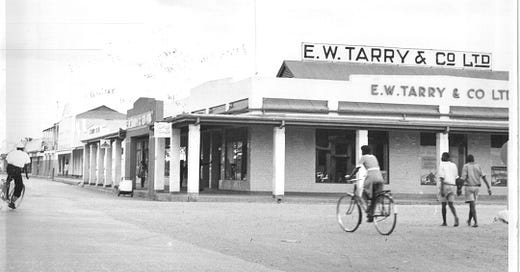

Everyday moments across Lusaka serve as springboards for this exhibition’s narrative, revealing how political independence, sovereign food production, and the circulation of goods continue to shape daily life. Going to Town highlights the infrastructure that sustains the city, with depictions of Freedom House, the NMC building, and EW Tarry. These spaces are not only functional but symbolic—Freedom House as a site of liberation and organising, the NMC building as a testament to food sovereignty and national industry, and EW Tarry as a marker of commercial exchange. Together, they chart the rhythms of a city built on movement, memory, and self-determination.

The latter is one of the earliest commercial structures on Cairo Road, the main commercial artery of Lusaka. Its name is drawn from the Cape to Cairo Road project, a colonial-era vision imagined by British imperialist Cecil Rhodes to connect British colonies from Cape Town to Cairo through a continuous road and rail network. Originally built to support Rhodes’ economic expansion, it played a central role in the colonial trade networks that facilitated the British South Africa Company’s influence in the region. Over time, the building changed hands, from its early commercial use to ownership by UNIP and later the Ginwala family. Once at risk of demolition, it has since been restored and recognised as a heritage site.

Today, it also houses the Everyday Lusaka Gallery, Sana Ginwala’s project that now has a physical space in the heart of the city dedicated to showcasing art grounded in everyday realities in the city. For this show, we focus on everyday routes, from Lilayi to Cairo Road, that reveal stories about Zambia that are lived but rarely formally showcased. The gallery’s present location feels poetic: a meeting point of past and present, where histories are made visible.

Oral History

One of Cecelia’s key works in this exhibition explores oral history and resistance through the figure of Zanco, whose story is immortalised in Zambia’s Freedom Statue. Unveiled in 1974 during the 10th Independence Anniversary, the monument honours Mpundu Mutembo, nicknamed Zanco, who famously broke free from his chains at gunpoint, refusing to remain shackled under colonial rule. His defiance became a national symbol of resistance, embodied in the sculptural form that stands on Independence Avenue today. Cecelia revisits this story through layered imagery and storytelling, drawing out the emotional and symbolic weight of Zanco’s gesture.

Another symbol that appears in her work is the bicycle. The known phrase “even independence was achieved on a bicycle” echoes through Zambian collective memory. Bicycles appear, not just as everyday objects but as emblems of resilience and grassroots mobilisation. It speaks to how nationalist leaders travelled across vast terrain to spread political awareness—humble yet powerful, the bicycle remains a symbol of agency and transformation in Zambia’s journey.

This transformation, both physical and symbolic, is best captured in Cecelia’s Cairo Road series. The city’s renewal, marked by the restoration of historical sites and the construction of new, locally inspired structures, is mirrored in these paintings as a visual echo of broader transitions in the business and governance sectors. The “Zamification” process entailed rebranding commercial and public institutions to assert national pride and self-reliance.

Roads such as Independence Avenue (formerly King George Avenue) and Lumumba Road (formerly Connaught Road) were renamed to mark the historic moments Lusaka took part in. In what Zambia’s first president, Dr. Kaunda, called the “New Africa,” these changes were conscious acts of solidarity that continue to reflect the country’s Pan-African spirit. At the same time, names like Cairo Road have been preserved, telling a broader story of connection and political alignment, anchoring Zambia within a continental and liberation-era narrative. Monumental edifices stand not only as urban landmarks but also as symbols of transformation, where memory converges with a vision for an independent future. By painting iconic and historic photographs of Lusaka, Cecelia offers a mirror on a rapidly changing city that remains to honour the full story of becoming and belonging.

Diasporic Belonging

I often remembered how, during the summer of 2023, the sunset arrested my restless, meaningless anxiety and engulfed me in beauty. Home felt like the most beautiful place, and simply being there made life feel meaningful. A vivid sunset is quintessentially Lusaka, as it signals the end of the day, “knocking off time.”

Home is like the sun, constant, ever returning, and grounding. This work captures the everyday experience of home through journeys on foot, minibus, car, or bicycle. Just as the sunset closes the day, it also gestures toward the promise of kwacha, a word that means “a new dawn” and is also the name of the national currency, anchoring hope in cycles of return, movement, and the quiet power of the ordinary.

In the same way, things started to make sense when I was home. In the community, the swinging door of care and presence wouldn’t allow what I’d normalised as just “being in a mood” to spiral. Like clues, parts of home came rushing back, sensations from my early years that never truly left. It’s reassuring, as part of the diaspora, to feel that home is just a flashback away. In unveiling Zanco and Cecelia’s stories, we hoped to show how personal and national histories intertwine, revealing how the city and the country at large have been shaped by many hands, voices, and lives. I hope those who see the show feel a trace of that belonging, that they can recognise something familiar and relish the richness of a heritage still visible in the city.

The Going to Town Exhibition at Everyday Lusaka Gallery runs from 17th May until 31st May. You can find more of Cecelia Miller's work online. Check out the Zambia Belonging Archive on Instagram and follow the gallery for all upcoming shows.

Read more on the Zambia Belonging Archive

I’m thrilled to read a piece about Zambia that isn’t on politics or its usual variations — economic development, self-help advice, business schemes, or big-name biographies. When politics does appear here, it serves to enrich the piece, adding flavor rather than being the through line.

This is the kind of writing I want to read more of about Zambia. I found the prose engrossing, and it covers ideas we should be spending more time reading, thinking about, and discussing. Ali A. Mazrui once spoke of a "triple heritage" in his excellent TV series The Africans — African roots, Western influence, and Islamic tradition. Unlike Mazrui’s East Africa, Zambia is shaped primarily by the first two. Ours is more a dual heritage, and your piece explores it with grace, insight and sensitivity.

I think these are the kind of ideas foundational to a culture that we should spend more time consuming and thinking about in Zambia. All the other wonderful things — building a country we can be proud of and that others can look to with respect — flow from a shared cultural identity. One we believe in, protect, and thoughtfully adapt. That work begins with curating our history, understanding it, and allowing it to guide how we move forward as a nation.