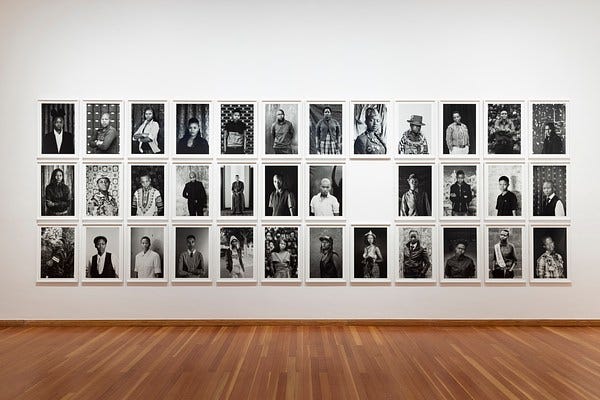

Zanele Muholi (they/them) is a South African visual activist and photographer renowned for documenting queer identity. Their acclaimed works, Somnyama Ngonyama and Faces and Phases, have been exhibited globally, including at the Venice Biennale and Documenta 13.

I was grateful to receive the exhibition book from Muholi’s 2020 Tate show. Having never seen their work in person, immersing myself in their visual activism was a gift. One that documents disruptions and feels especially urgent today. As hostility toward marginalized identities grows, Muholi’s work reminds us that queerness is not just about identity but about care, resistance, and claiming space. Their images demand recognition, not just for those they portray but for all of us.

This felt like a fitting read in light of some of the thoughts I’ve been having about the increased hostility towards the LGBTQ+ community and the rise of fascism in Europe. It underscores the urgent need for works like Muholi’s to be shared in-depth, as they challenge such harmful narratives and provide a much-needed visual representation of the “other” as a counterpoint to the rising tide of fear and division.

It’s the confrontational nature of Muholi’s photography that urges but also exclaims I am here - we are here. Their subject matter takes centre stage, and similar intention rests in their choice of colour and composition, as the black-and-white leaves no space for whimsical distraction. One must absorb everything, as they often look straight back at us. Like Carrie Mae Weems, Muholi presents themselves within their work, using the intimacy of their gaze to insist that the viewer bears witness. Their subjectivity is undeniable, and their presence commands attention.

Capturing the Community

Muhole is dedicated to documenting/unboxing those along the margins. Along with the Muholi self-portraits series, they have captured the LGBTQI+ folk in South Africa. They seek to preserve and archive the community's life at weddings, funerals, and public spaces (often under the threat of danger).

Their context: South Africa, despite its progressive legal framework, remains a place where queer individuals face discrimination, violence, and social exclusion. Hate crimes, including so-called "corrective rape" and homophobic attacks, are stark realities that persist, particularly in townships and rural areas. The work of Muholi and their peers serves as both an act of resistance and a testament to the resilience of this community in the face of structural and everyday violence.

Series such as The Pageant, Somnyama Ngonyama, and Faces and Phases focus on documenting these intimate and powerful moments, allowing a fuller picture of the strength, beauty, and survival of queer lives in South Africa. By archiving these stories, Muholi affirms their community's existence and challenges the erasure and systemic oppression many continue to endure.

"I am re-writing a black, queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our existence, resistance and persistence," says Zanele Muholi.

Coloniality and the Margins

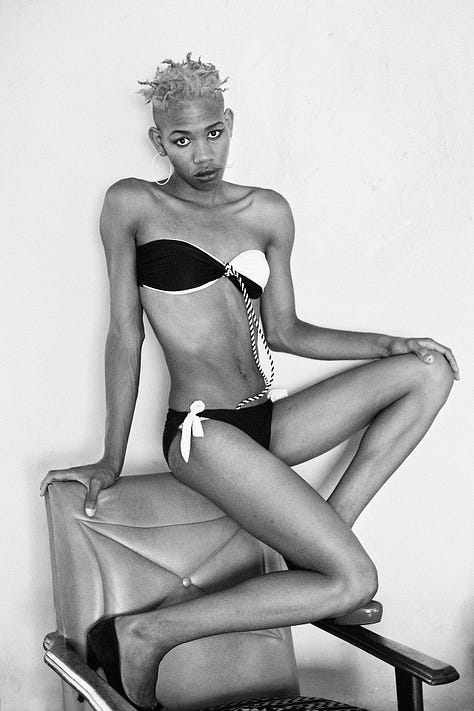

The Pageant, in series particular, reclaims visibility and joy in a society that denies both to queer individuals. Through beauty pageants, Muholi captures defiant self-expression, dignity, and resilience—challenging exclusion while asserting the right to exist in public space.

The power of photography allows Muholi to transform the reality of participants’ place in the world while documenting evidence of these realities. Although apartheid officially ended, its categorizations and hierarchies persist. And at the bottom of this structure of otherness and marginalization remains the queer community. Muholi has also documented to bear witness and corroborate the abuses they face, institutional failures, and difficulties in attaining justice. Capturing pain, intimacy, joy, and future, they have co-created work that inhabits a broad range of emotions and phases of their communities.

They describe their work as more of a co-creation and refer to participants rather than subjects. Working from an insider's perspective, they rarely interview strangers, instead engaging with people familiar to them—a wider community of friends and friends of friends.

Visibility is Muholi’s tool towards justice, as stigma fails to silence the community. By granting access to these testimonies, participants are transformed from victims into more than just subjects of violence—they become truth-tellers and, in a sense, public prosecutors. Here, the archive functions as activism.

If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

-Zora Neale Hurston

Liberal Diversions

I believe there is a need for Muholi’s work beyond South Africa, and it is my joy to see their work celebrated globally. While liberalism, in an 'all lives matter' fashion, makes an effort to include otherness, it lacks the ideological backbone to follow through. Something that will be crucial in today’s increasingly hostile political climate. I’m particularly concerned about the culture of care that liberalism promotes and its limitations in actively holding space for the other. This has been a struggle, especially in celebrated liberal societies like the Netherlands, where I spent part of my upbringing.

Normative assimilation of culture and identity accommodates different 'boxes' of identity but doesn't address the building blocks for cohabitation, which requires active care, understanding, and dialogue between those boxes. Simply “allowing” you to have your box frames tolerance as temporary, as if it’s a ticking time bomb. Instead, we should move beyond mere tolerance. "I tolerate you" is not the same as "I respect you, I see you, and I stand with you."

One of the significant challenges of such assimilated or liberal cultures of acceptance today, revealed to me in so-called “strongly worded debates,” is that we don’t promote a community of care. We promote a community of boxes and isms. It’s a "not in my backyard" mentality, which becomes glaringly obvious in supposedly progressive yet exclusionary wealthy suburbs and even more so in cities—the supposed liberal melting pots.

Insiders, by which I mean those with the luxury of a lack of shame, will engage in conversations where (age-mates) casually justify fiscal conservatism as if it were Coke Light when, in reality, it’s Coke Zero = zero empathy, zero responsibility, zero fuc*s given to the margins. The avoidance in these discussions is striking: fiscal conservatism isn’t just about limiting taxes; it has a funny way of conveniently limiting rights.

Do we understand that our liberal politics lack the backbone if they fail to fundamentally denounce—not just in words, but in action—the systemic barriers that limit others' existence? I’m fun at parties, as you can probably tell. But what does it even mean to be “liberal or progressive” if the very structures we claim to uphold are built on the backs of the marginalized, both economically and socially?

Queerness Will Save Us All

Rather than relying on a liberal notion of inclusion, we can adopt a queer politics of care. One that foregrounds mutual aid, solidarity, and resistance to oppressive structures. True inclusivity does not come from merely expanding existing categories but from dismantling the hierarchies that confine us.

Queerness can be broadly defined as a rejection of fixed, normative identities and a challenge to rigid categorizations of gender and sexuality. It embraces fluidity and nonconformity, resisting binary thinking and fostering a relational culture rooted in connection rather than rigid classification.

As a political framework of care, queerness moves beyond individual identity to emphasize relationality, interdependence, and collective well-being. It challenges systems of exclusion and prioritizes creating spaces where marginalized identities are not just tolerated but actively cared for.

Muholi’s activism embodies this ethos, intersecting issues of race, class, and gender. Their work reminds us that queering is not just about identity—it is a mode of resistance, a challenge to the status quo, and a force that can shift power dynamics to create a more just and compassionate society. Queering demands that we break free from conventional expectations, creating space for those who have been marginalized or silenced. In this sense, it does not merely advocate for LGBTQ+ rights but calls for a broader restructuring of society that centres on care, justice, and equity.

Their images serve as provocations toward liberation—an insistence on freedom, self-expression, and the affirmation of identities beyond societal constraints. Muholi’s work is not just art; it is a community-building practice, with participants and the artist collectively shaping a campaign for acceptance, understanding, and equity. The sheer presence of their work across various platforms reinforces this message, demanding recognition through its frequency and visibility.

Collectivity as an Ethical Imperative

At the core of queering our ethics is empathy. When we deny others the right to self-identify, we also diminish our own space for self-expression. Bigotry does not exist in isolation. It thrives on the gradual erosion of empathy. Tactics such as dismissing people as "snowflakes" undermine the validity of care and understanding, making vulnerability a target rather than a strength.

As Selda Koydemir notes

being labeled as sensitive for reacting to disrespect is a form of manipulation.

This is about dismantling imposed boxes and reclaiming identities that have transformed, engaged, and educated the public. Visibility is fundamental. Learning and actively fostering a culture of empathy, often dismissed as "wokeness"—threatens those who seek to conserve limiting social and economic rights.

Queering, as a radical act of empathy, creates space for coexistence across all walks of life. It teaches us to think beyond rigid binaries—whether in identity, constitutionalism, or the classist foundations of fundamentalism. It asks us to lead with our hearts rather than adhere to inflexible ideas that strip us of the humanity we owe each other.

Queering will save us all.

Muholi's exhibition at Tate Modern in London concluded on January 26, 2025. Their work is currently featured in several exhibitions worldwide:

SCAD Museum of Art (Savannah, Georgia, USA): From February 24 to July 6, 2025, the museum presents a selection of Muholi's works, including pieces from the Somnyama Ngonyama series.

IMS Paulista (São Paulo, Brazil): The exhibition "BELEZA VALENTE" will be on display until June 22, 2025.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art (Brunswick, Maine, USA): An exhibition featuring Muholi's work is scheduled from January 16 to June 1, 2025.