The African Facade: Ethnographic Collections in Europe.

From You Hide Me to Dahomey and Julien’s Vision

The archive is never a neutral space despite the “owners'” objectivity. Such an understanding would assume the objects are passive, merely collectibles, and even that would assume they are embedded in some value, should they be displayed. This shifting in meaning around the museum and agency of its objects has occupied my mind over the last months while I have consumed different films as reference points.

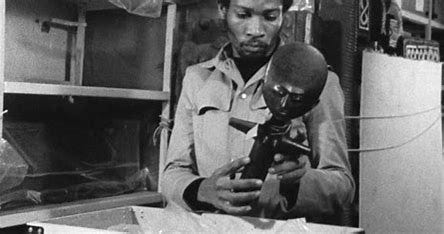

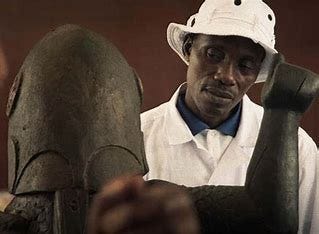

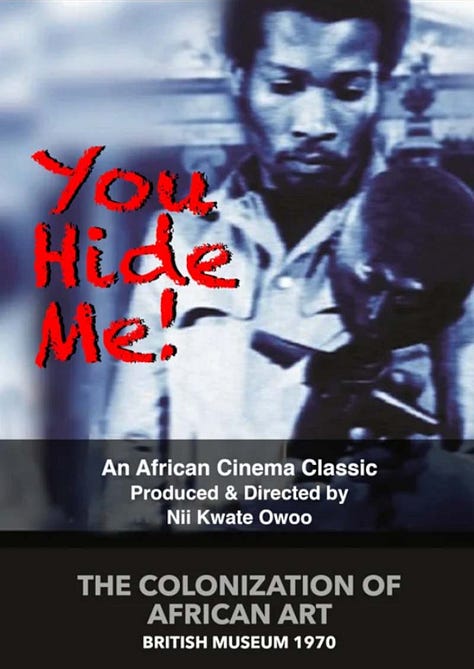

Reference one: Nii Kwate Owoo’s You Hide Me

Ghanaian filmmaker Nii Kwate Owoo’s 1970 documentary You Hide Me reminded me of how this question has not aged. The first function here seems to be the idea of the museum as a clearing house of meaning; the objects are cleansed of maker and origin and neatly laid out for safekeeping. The majority are not displayed but stored, sometimes less meticulously than priced objects would be. As a trip to the British Museum unfolds, Owoo’s show-and-tell evolves and attempts to answer the question: Why is Europe still filled with ethnographic collections?

In You Hide Me, Owoo exposes how looted African artefacts are stored in museum basements in a hoarder-like fashion rather than properly exhibited or returned. His work calls for the rehabilitation of African art—its restitution to Africa and restoration to its rightful place in history.

In this instance, ethnographic museums can be seen as presenting merely “The African Facade”—a stripped-down version of objects displayed in Western institutions, detached from their original cultural, spiritual, and historical contexts. Owoo argues that these collections function as a facade, reinforcing the idea that African art is primitive and static. This detachment is not neutral; it is an active exercise in erasing meaning and reinforcing colonial narratives that cast Africa as a passive subject in the story of European civilization.

This ongoing detachment has lasting consequences. Generations remain disconnected from their origins and cultural wealth when the objects themselves are missing. Though these histories are still written about, remembered, and circulated within Africa, most of the artefacts remain physically located in the US and Europe, out of reach from the communities to whom they belong.

In a 2021 interview, director Nii Kwate Owoo spoke candidly about how he had to pose as a gentleman in a borrowed three-piece suit to gain permission to film inside the British Museum. The film was initially presented as a respectful portrayal of the institution’s efforts to “preserve” African artefacts. However, filmed clandestinely, You Hide Me does the opposite: Owoo dismantles the colonial narratives of preservation and issues a clear call for restitution.

Reference two: Mati Diop’s-Dahomey

There is a spiritual obstruction in Mati Diop’s 2024 Berlinale-winning film, which, though set in the present, reflects on the enduring impact of the absence of spiritual monuments and the colonial vilification that accompanied their removal. The film brings to the foreground the functionality of looting within a religious scope. Religious objects were taken as part of a broader effort to discredit and suppress local religions. The return of such an artefact also opens space for dialogue on colonial crusading and spiritual revolution. Voodoo, once a respected practice, is now widely vilified. Some participants in the dialogues the film follows even fear the idea of particular objects returning, fearful of their power and the potential blasphemy tied to reclaiming a native spirituality that had long been suppressed-difused.

The documentary explores the broader scope of restitution by following the return of looted objects from France to Mali alongside the public dialogues and perceptions surrounding their repatriation. This time, Mati Diop gives the artefacts a voice. Dahomey is an influential visual spectacle in its subject matter and distinct narrative perspective. Diop evokes a sense of claustrophobia that mirrors their long, dislocated journey by allowing the artefacts to speak. At its core, the film examines themes of restitution, homecoming, and freedom. Freedom from the museums in which Europe takes pride and the colonial narratives that have shaped the continent’s history.

One might expect that, in the spirit of good governance or the democratic ideals often championed by the West, the return of looted artefacts would be straightforward. Yet the process remains slow and selective, exposing persisting, deeper power imbalances. Diop’s short film conveys a sense of disbelief about this: How can African leaders possibly accept the conditional return and or ransom of stolen cultural property?

Unrivalled Art and power play

Building on this, it’s difficult to cleanse the museum’s name as a colonial institution, and I’m holding back from mentioning the Africa Museum in Tervuren. Were these spaces ever meant to be neutral, or were they always, at their core, imperial institutions? The more I reflect on this, the more I see how their grand halls and glass cases often tell a story of power, objects taken, displayed, and made to serve a particular narrative.

The display indicates power relations, subjecting objects to new interpretations and explanations. The institutional direction of meaning-making divorces these objects from their makers and memory. This authoritative system of ownership and exclusion puts the European expert in an intellectual monopoly over African art and its creators or preservers. Africans are often depicted as uneducated about their own culture, and the educated European steps in to interpret it. However, European practice has been primarily one of conservation, theorizing, hypothesizing, and categorizing objects looted from their original source, a process that mirrors colonial practices.

The idea that the West can define what is African is as ironic as colonialism itself. For example, no African museums offer an African explanation of what Europe is, let alone display stolen European objects. Owoo touches on this paradox: once labelled as primitive, Europeans now regard African art as "unrivaled”.

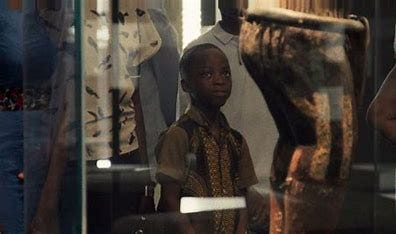

Yet, the notion that these extracted objects could serve as proper "education" is deeply flawed. A particular scene comes to mind: a parent with their young children stands before an African artefact, attempting to familiarize them with what is African. "There are many animals in Africa... oh, that’s an African drum! Yes, Africans are very musical..." They move on to musical instruments, then to the next display, you get the picture.

The notion that 'Africa' can be neatly placed in vitrines for the voyeur’s gaze... I don’t know, man, it’s a lot. Owoo’s You Hide Me argues that the heritage collection was deeply intertwined with the ideology of colonialism.

The African Façade also alludes to the idea that African history, culture, and customs must be diluted and fed back in a governable version acceptable within the frameworks set by former colonizers.

In this massive collection, seen in You Hide Me, the valuable objects are unveiled as if it was a Hoarders episode, revealing the vast expanse of African art stolen by English colonial ventures. Its function Owoo further describes the “African Façade”. As a version of Africa deconstructed by the colonizer, its history twisted, its cultural artefacts stripped from their context and displayed in ways that reinforce Western ideas of ownership and authority. What makes my ear itch is the unsettling realization that these objects, once part of living traditions, now sit behind glass, frozen in time, their meanings reshaped by institutions that were never meant to hold them.

Owoo’s ability to deliver this crux within the limited time of a short film is incredible. We can tell he didn’t just “gentleman” himself up for that interview; he truly finessed the institution, demonstrating a deep understanding of what he wanted to say and his assessment—not just of the museum’s formal function but of its present exercise. After all, why hold objects for ransom if they no longer have value today?

Some of these so-called “primitive” objects were, in fact, the blueprint for many celebrated Western artists. I’d invite you to follow the spiral of Kirchner and his wife’s time in the tropics—though that’s a story for another time. Kirchner is a prime example of this pick-and-mix vibe: drawing freely from Indigenous forms and aesthetics while stripping them of their original context. This selective showcasing of specific works over others often carries a signalling function, creating a visual contradiction to Western modernity. Even in praise, African objects were framed as exotic inspiration—primitive, raw—while their own royal and grand nature was sidelined.

I felt uneasy after seeing a set of Benin wooden carvings displayed alongside Picasso’s work at the L’Orangerie in Paris. Though the label credited “inspiration,” the context wasn’t about shared artistic exchange if the maker can’t even be named. Paintings like Picasso’s are, in many ways, copies, flattened interpretations of spiritual, intricate works.

Iconically, Owoo ends You Hide Me with vibrant footage from a royal celebration in Ghana, reclaiming space, pride, and ceremony. It’s a bold demand for the immediate return of African-held objects—set not in a museum but at home, where they belong.

Reference three: Isaac Julian’s ONCE AGAIN... (STATUES NEVER DIE)

In similar future thinking, Isaac Julien’s 2025 film delves into the complex relationship between Dr. Albert C. Barnes, an early US collector and exhibitor of African cultural artefacts, and Alain Locke, the renowned philosopher and cultural critic known as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” I first encountered this work during his exhibition, What Freedom Is to Me, at the Bonnefanten in Maastricht, where Julien’s layered storytelling really stood out. Like Owoo’s You Hide Me, Julien’s film opens a conversation about the absurdity of how African art has been revealed and framed. It critiques how European ethnic culture specialists have historically controlled the narrative, dictating what is considered the most advanced while ignoring the origins of these artefacts and the looted circumstances in which they were taken.

His blend of fiction with historical facts creates a sense of unmutilated unity, imagining histories where civilization thrived, untainted by the spectacle of exploitation- the African emotion in a new setting. Julien’s work is a conversation with a counter voice, reducing the African façade through the lens of Locke. It presents the idea of the museum as a space for exchange, a space for actively creating awareness. While the backdrop remains the vitrines, there is a circular movement of meaning-making. Julien proposes a structurally different system for decolonising with the archive. It is within this setting that newer forms of curation encourage the public to reveal personal and individual relationships to the structures and systems of power housed within the museum.

Julien’s vision offers more than critique; it offers a blueprint. By placing Black voices at the center and engaging history through a lens of possibility, he invites us to imagine museums, archives, and futures that no longer speak about Africa but with it. Alongside Owoo and Diop, we see not only a critique of institutional power but the emergence of new cultural blueprints. Their work challenges how we remember, who gets to narrate, and what restitution might truly mean. In their hands, the archive becomes a site of resistance—and the future, a space for radical reimagination.

There’s so much work at the moment that I’m excited about, and I can’t wait to share more with you. Let’s embrace this imagination while engaging history in meaningful ways. Perhaps this is the next step: not only to return what was taken but to reimagine what can be built in its place.

Explore

Isaac Julien | Artist Interview | Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die) | 2024 Whitney Biennial

Nii Kwate Owoo on his film You Hide Me (1970)

DAHOMEY | Official Trailer | 2024