I recently had the honour of writing the exhibition text for a solo exhibition at the Everyday Lusaka Gallery in Zambia. A deep longing for home, history, and artwork that feels authentic made this assignment a perfect fit. Initially, I had planned to focus on writing about just one piece if I liked the work. However, I wrote most of the exhibition text and artwork captions. I even had an extensive phone call with 1Ba Chikwa one afternoon as he added some final touches to the work. Needless to say, I became deeply invested in the exhibition and the journey of the artist's creations.

Lawrence Chikwa (b. 1973 Chingola) is a dynamic artist whose practice spans Zambia, the African continent, the United States, and Europe. He established Inter Art Studios in Lusaka in 2007, cultivating a professional discipline that attracts local and international collectors. He continues to work in his studio in Chongwe, Lusaka, collaborating with art galleries and cultural institutions. His work is celebrated for its ability to bridge local and global narratives, making him a significant voice in contemporary African art. His latest work touches on the topic of independence, on which he shares observations about national history and trajectory to the future.

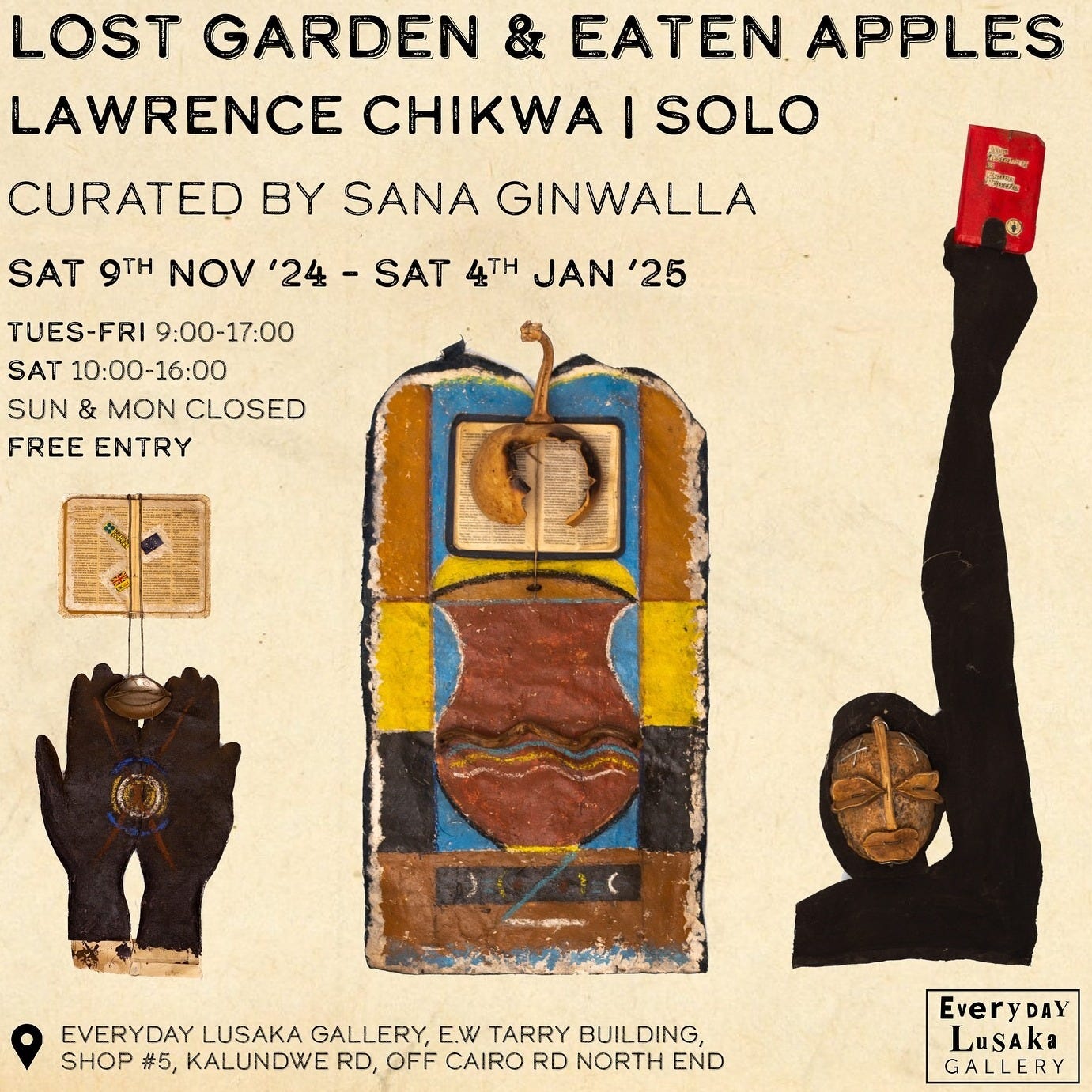

Lost Garden and Eaten Apples

Lawrence Chikwa’s solo exhibition Lost Garden & Eaten Apples reflects on Zambia’s journey as a post-colonial nation, openly questioning Zambia’s classification as a so-called “Third World“ nation. The exhibition title uses the image of a mythical garden to symbolize Africa as a once-lost paradise—a place with a bitter past, where its people question whether they must continue tasting the bitterness of past struggles or seek new means to cultivate a different future. By crafting and weaving this layered narrative, Lawrence Chikwa’s diverse body of work evokes the imagery of Zambia’s journey and the shifts between modernity and nature, traditional practices, and symbols of power.

For Ba Chikwa, Zambian history is closely tied to British imperial expansion, driven by missionaries and explorers seeking cultural, political, and economic wealth through territorial conquest. However, the benefits of this expansion have not fully materialized, as Zambia struggles to catch up in today’s fast-paced globalized world. For sustainable development, it is crucial to incorporate local values and interests.

Evolving Narratives

Many pieces included in the show were not created solely for this exhibition but have developed over time as Ba Chikwa’s experimentations and explorations of the subject matter have deepened. This exhibition unites that journey, not to repeat past themes but to let the work speak more. While Ba Chikwa’s early iconic style was rooted in classical abstract paintings, this exhibition turns towards the evolution of his practice.

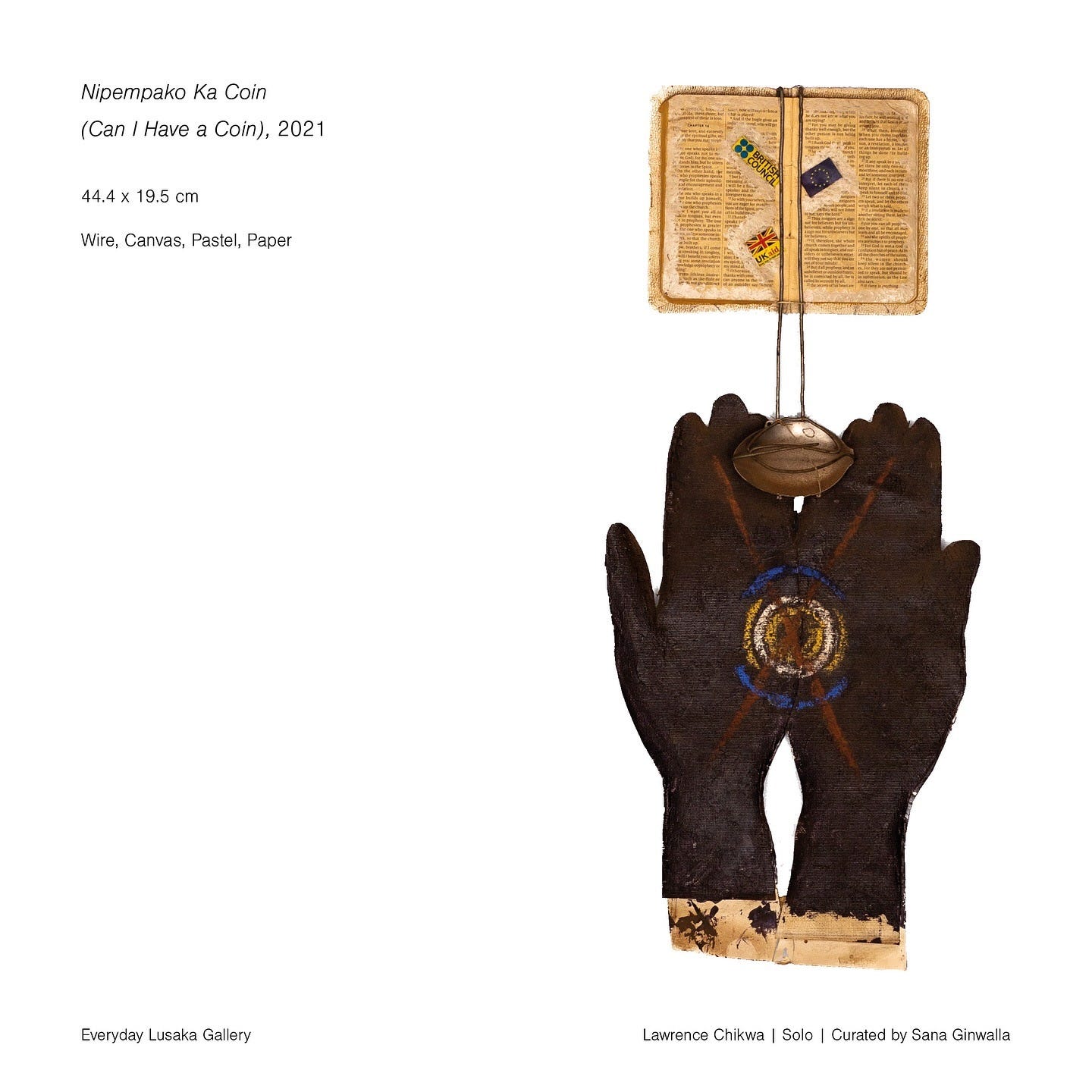

On the phone, we spoke in depth about how his artistic practice was shaped by his education, his institutional conditioning- what was believed to be “African art"- and his eventual grounding in creating art within the context he knows best. In his work, we see objects deeply rooted in this exploration of key themes from his present moment and observations. Materialising these themes in the object, he recreates this journey. Working with non-traditional materials ranging from mundane objects such as seeds, pods and scrap metal to more sensitive materials such as Bibles and banknotes, Ba Chikwa works with materiality that has become distinct in his style. These objects represent the history and the influence on Zambian society, where questions of power and self-determination run through the use of Bibles and banknotes.

Shadow of Hope

Each piece was a pleasure to indulge in, savouring its layers. It was also an indulgent process to preview the work and discuss it with Ba Chikwa. I’ve written about many of the pieces in the catalogue. There’s one piece, in particular, that I’m especially fond of. I first spotted it in a video of the artist’s studio, and intrigued, I inquired about its inclusion in the exhibition. I regret not buying it after reaching my annual ceiling for art purchases. My favourite piece is "Shadow of Hope," which depicts Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding father and first post-independence president—a familiar figure in Ba Chikwa’s work. He represents Zambia’s struggle for freedom and the creation of collective belonging in post-colonial Zambia. His legacy endures, symbolizing historic pride and the nation’s ongoing evolution.

Although independence has revealed diverse views among different generations and their descendants, colonial pessimism diminished confidence in the past and future-making. Lost Garden & Eaten Apples is a commentary on the burden of this history, unveiling what lies behind the scenes of a linear narrative about progress and rights. It reveals the brutality of colonial imperialism on current forms of exploitation of natural communal relations and ties while placing the responsibility and possibility on raising Indigenous heritage practices to transform colonial heritages – so that, one day, the people may eat apples without the lingering bitterness of past struggles in a place of free-living, all found green and uncircumcised.

Introduced by Kenneth Kaunda, Zambian humanism blends traditional African values with Western socialist and Christian principles to emphasize human dignity, communal living, and social justice. It also incorporates nature and mythology, creating an inclusive, holistic worldview. This philosophy helped unite Zambia, supporting the UNIP party’s liberation ideals and shaping the country's socio-economic framework, reflected in the 'One Zambia, One Nation' motto.

Kaunda’s humanism countered colonial ideologies of racial superiority, offering a path to true independence. It encouraged the creation of a unique political system, integrating local beliefs and rejecting Western imitations. Today, this philosophy remains a legacy, still relevant as Zambia celebrates 60 years of independence. For Ba Chikwa, this vision aligns with the ongoing struggle for economic autonomy and a nation's growth rooted in its history and identity.

As a conceptual artist, Ba Chikwa’s work carries profound depth and complexity. He weaves a historical timeline through his commentary on Zambia’s colonial history and current societal conditions. He further explores how individuals protect themselves by calling upon spiritual and higher powers in prayer or spending one’s money to hire this desired power for physical protection. Thus, Ba Chikwa examines the consequences of history and the changing ways we perceive nature, doctrines, religion, and future perspectives within a contemporary capitalist framework.

A Third Space

The venue for this exhibition was equally remarkable. To me, the charm of The Everyday Lusaka Gallery is in its relational authenticity—an alluring space designed as a true third space. It’s a free and open venue where visitors can recognize the space as their own, with art not only on view but woven into meaningful dialogue. Answering my question for this year, “Art, and what about it?” in a remarkably thoughtful way. Well, what about art for the people, by the people—not in a Marxist utopian sense, but something close? Art can serve the purpose of sharing and showcasing community.

The gallery's location in the historic E.W. Tarry Building adds to its unique dimension, blending contemporary art with its rich colonial history. This juxtaposition created a space where art is accessible, inviting art enthusiasts and passersby to engage with the works on display. During the colonial period, British settlers built structures that reflected European ideals and social hierarchies, contrasting with traditional African architecture. The E.W. Tarry Building symbolises this colonial influence, reminding us of Lusaka’s colonial past.

Located in the city's heart, not tucked away in an affluent neighbourhood, Everyday Lusaka Gallery engages with this history while contributing to Zambia’s modern cultural and artistic landscape. The blend of contemporary art in a colonial-era building sparks a dialogue between past and present, reflecting the ongoing process of reimagining identity in post-independence Zambia.

This ethos is curated by the founder, Sana Ginwalla; I deeply admire Sana’s intent to highlight the beauty and history of this divine city. Sana is a Zambian-born photographer, curator, archivist, designer, and writer with roots in India and Myanmar, and she explores themes of identity, home, and belonging through her work. Her creative vision provides a nuanced visual representation of Zambia. In 2018, Ginwalla launched Everyday Lusaka, an art platform dedicated to presenting a thoughtful and considered visual narrative of Zambia. Now expanded into a gallery, the project seeks to spotlight overlooked yet relatable moments—past and present—in Zambian life. Through her archival work and its continuation via the gallery, Sana decentralizes the history of Lusaka and Zambia, offering fresh perspectives on personal and collective narratives.

HomeGrowing and HomeGoing

The gallery embodies the essence of homecoming, homegrown creativity, and celebration—a somewhat radical act in a world where globalization often entices us to look outward for solutions. Everyday Lusaka chooses to remain rooted at home, welcoming all with open doors, free of charge, in the spirit of Zambian kalibu (hospitality). More precisely, it channels the dynamic Mukwela demeanour—commonly used by Lusaka bus conductors to signify motion, inclusion, and readiness to journey together—right in the heart of the bustling capital.

I won’t dive into a deep political-sci chat about the pieces here (though, for the record, it’s in my Hinge profile—and yes, red wine in hand does get me going). Instead, I wanted to share more about the experience of attempting to conceptualize rather than being on the watch for curatorial finesse. God knows I’ve hoped no one saw the exhibition and felt “finessed” themselves.

The experience was, first and foremost, about understanding—putting words to the authenticity of the journey, both in its specific context and its universality. I shared a message with the subtle depth of an “if you know, you know” tone. Second, I avoided over-problematizing the work, knowing that its weight can only be fully measured by the public. Instead, I focused on centring the point I shared with Ba Chikwa: a revolutionary imagination and a resolute celebration of the garden's beauty, even in limbo, where the garden remains a paradise. This intent felt essential—not just to the context but to the space and what I believe is the actual function of art. I otherwise have no endurance for art that beats you down with the harsh realities of life and leaves you without any aftercare of thought.

Writing these words has easily been a highlight of my year of Art-gallivanting—giving written context to the art and ideas that emerge from layered creative exploration. It’s been an especially curious, homegoing, and enriching experience, writing within the context of a culture that feels familiar and new as I discover and reencounter it. The prefix Ba, which you’ll notice throughout the text, carries significant weight and reflects the profound honour I felt in writing about this work. I couldn’t write about someone whose work I deeply respect without it. It’s a cultural way of recognising our elders while also praising their place in the collective memory of cultivating the garden—the ultimate third place that is home.

This exhibition is on at the Everyday Lusaka Gallery in Lusaka, Zambia, until January 4th. The community has given it a great reception, and it is a rich learning experience.

For more information about Sana Ginwalla's archive projects and the Everyday Lusaka Gallery, visit her official website and follow the Gallery online.

In Bemba (a language spoken in Zambia), the prefix "Ba" is an honorific title that conveys respect. It is often used before a person's name or title to show esteem or respect. This honorific is a key aspect of Zambian linguistic and cultural etiquette, reflecting the importance of showing respect in social interactions.